On 4th August 1914 war was declared, and on the 12th the Secretary of State for Scotland decided not to re-arrest Ethel whether she had broken the conditions of licence or not, but to remit remainder of sentence. [i]

All suffragette prisoners were amnestied and the WSPU was disbanded. The Pankhursts backed the war with jingoist fervour and others looked around to see what they should do next. Before they were called in to work in munitions factories to replace the men who had enlisted many women were thrown out of work, so the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), which had kept its organisation intact, started a new, London-based, National Service Organisation (NSO) to bring women and employers together and to make sure women were not exploited. Fanny Parker was appointed honorary organiser, with Ethel as her assistant, despite the fact they had been WSPU members. Following a visit by Fan another branch was formed later in Glasgow, where Janie Allan was doing the same work with the Scottish Council for Women’s Trades. Arabella got married and emigrated to Australia. Lila Clunas threw herself into local politics. May Pollock Grant signed on as a VAD nurse at Caird Hospital and Mary Henderson went off to help Dr Elsie Inglis in her battlefront hospitals. The less militant suffrage societies seem mostly have turned to the relief of distress of wives and children left without support in the absence of their menfolk; the Women’s Suffrage National Aid Corps was formed with branches in Edinburgh & Glasgow; and the WFL turned their shops into workrooms for the unemployed, to make clothes for Belgian refugees. However new groups grew from the old; the WSPU formed the Suffragette Fellowship and the WFL kept its organisation intact until the 1960s.

Fan and Ethel set off for London, where their new NSO office was based at 144 High Holborn, with the Emily Wilding Davison Club/Lodge above. Charlotte Despard, President of the WFL, introduced them to the readership of The Vote in June 1915: “We appeal to our readers to make known the new organisation and its purpose – which is to find the right work for the right woman – and we advise all women, desirous to serve in the national crisis, to enrol as members.” Fan and Ethel then added their paragraphs –

‘LET’S ORGANISE OURSELVES!

One great reason for demanding the vote … is to improve the position of women. The great handicap to the advancement of women is their financial dependence. Man in possessing himself of all the good things of the earth has set up a standard of value. The standard is his pay, his income, his possessions. …no such value has been placed upon the service of women, who have had to put up some stiff fights during the last century in order to secure the recognition of their services according to men’s valuation…. At the present moment we certainly have an opportunity of improving the economic position of women. Men are wanted to fight for their country, and in most cases their places can be ably filled by women wishing to take their share in the work of the nation. …There is no lack of women volunteers, but there is a demand for organisation. At present there is not only chaos but there is also danger. There is the danger of the voluntary worker who disregards the claims of the woman who is dependent upon her work, and the danger of the worker who, by taking the lowest wage, brings down the whole standard of living. … Numbers of educated but untrained women, desiring to “do their bit” have undertaken all kinds of unsuitable work… For instance, Mr Asquith, soon after the war broke out, kindly permitted women to become agricultural labourers; some towns are permitting women scavengers…

Let us organise ourselves in order that we may be enabled to take our proper share in carrying on the work of the nation

Let us organise ourselves in order that we may watch more closely developments that affect women’s work

Let us organise ourselves in order that we may be united in demanding a fair wage

Let all women who desire to work enrol as members….’

Ten days later a more urgent message was published in The Vote: ‘There is no doubt that the Government, in dealing with the problem of munitions, is not employing workers registered at the employment exchange to any extent but an endeavour is being made to collect voluntary women workers with the help of some women’s societies. We heard a few days ago that an employer enlisted the help of one of these societies to collect women workers and then explained that as they were untrained women, of course, they would be unpaid.’

Women were now working in a variety of jobs, as dispensers, on railways (with equal pay), as postwomen, park keepers and fruit pickers. At a meeting of the Women’s National Service Organisation in the Kingsway Hall on 10th September 1915 chaired by Mrs Despard two men and two women (including Fan’s mother) spoke to the title ‘Women & Work’. Fan and Ethel were praised; it was said: “The competent women who direct the work inspire an immense confidence by their keen intelligence, lively sympathy and brisk business capacity”.

Fan and Ethel had clearly not lost their campaigning spirit. But I have found no record of how the NSO progressed. Ethel was still in London the following year, because she exhibited paintings at the RSA and the New England Art Club which were submitted from London. There is also a painting by Ethel in Missouri USA, dated 1915 or ’16 (the writing is not clear). It is of a spaniel, in an oval frame, and looks as if it was painted for the fond owner of the dog. Could it have been for someone who was travelling to North America and had to leave their pet behind? Some of Ethel’s Moorhead cousins lived in Minnesota (about 600 miles north of Missouri), but they had gone there long before 1915, so that possibility is remote.

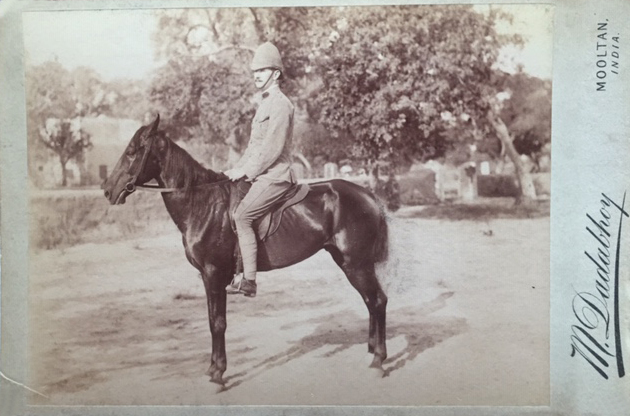

As for the rest of the family, Arthur had done well in his career in the army. He served in France in 1914 with the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division, being promoted Lt Colonel in July and Brevet (temporary) Colonel in Feb 1915, and was awarded a DSO. But it was not to last. He contracted TB and was invalided out, and went to Somerset to stay with his brother Rupert in Batheaston. He died on 1st March 1916, aged only 44, leaving his estate of £2152.11.8 net in trust for Ethel. This would have provided her with an income of about £100 p.a., whereas something more like £250 would have been necessary to live comfortably at that time. Arthur appointed Rupert and Fred Shum, solicitor, as the executors for his will; he probably did not trust Ethel to budget wisely, and in this he was very likely correct; she was generous with her money, she dressed fashionably and travelled widely and, like many of the family, she liked to gamble.

George Oliver’s sons joined the war effort. George Brian served with the South African forces in East Africa. 20-year-old Sidney Patrick (‘Paddy’) came to Sandhurst to train as an officer in 1915. He remembered: “Miss Parker was the niece of Kitchener, her mother being his sister. She was going great guns in 1915 and early ’16 when I met her when she tried to forward my career as a newly commissioned officer.” Fan (or possibly Ethel) arranged for him to meet Kitchener and he spent a weekend at Aspall Hall in Suffolk, the Kitchener’s home. [ii] He went off to serve in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). By 1916 Henry Kitchener had succeeded his famous younger brother as Earl; he wrote to Ethel from Tanganyika saying he would certainly help Brian if he could. He added:

“Let me know when Fan’s portrait comes on for show. WHAT a crowd there will be! THE FIRE BRAND in REPOSE!! I have asked my friend and partner Capt Mundell to call and take you and Fan to the theatre for me when he gets home.”

It is not certain where Ethel was and what she was doing between 1915 and July 1922. She kept her studio in Dundee until 1916 (if the Street Directory is accurate). In 1918 she was in Dublin; she exhibited Lady in a Chinese Coat at the RSA in 1918 and Portrait of a Lady in 1919, both submitted from 5 Burgh Quay. The Dictionary of Victorian Painters records that she also exhibited in Dublin, though there is no record of any of her work at either the Royal Hibernian Academy or the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery. In 1918 she rented a house called ‘Windgates’ in Wicklow, and painted landscapes there which she was to reproduce later in her journal This Quarter. In 1920 she submitted two pictures to the RSA from Bonnyton House, Arbirlot (east of Dundee).

Both houses could have been peaceful venues for painting. Bonnyton House belonged to Alice Moorhead’s partner Dr Emily Thomson, who was carrying on the medical practice on her own. Emily was interested in the arts and was to be found at many viewings. She had bought Bonnyton House in 1914 from a farmer’s widow. The house was quite small and jammed with her collected works of art and antique furniture, but with big grounds graced by specimen trees planted by Lord Dalhousie. Nearby in Arbroath was a thriving arts centre. Emily retired in 1922 (age 58) and did some painting of her own.

Ireland is another matter. It was about a month after Ethel’s brother Arthur died in March 1916 (she was in London then) that the Easter Rising occurred. The Easter Proclamation was as revolutionary in its inclusion of women as it was in other respects. It made its appeal to Irishwomen as well as Irishmen, and promised universal suffrage, ‘equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens’.

In April 1918 the Conscription Bill caused outrage and was met with violent resistance.

In January 1919 an Abstentionist Parliament (Dail) met in Dublin, and passed a Declaration of Independence even though half its members were in British jails. Dail was declared illegal in September. There were more than 87,000 British troops in Ireland, killings, imprisonment, espionage and counter-espionage were everywhere. If Ethel was not involved in politics it is not surprising that she retreated to the Wicklow Hills. But IRA member Erskine Childers lived in Wicklow at his home, Glendalough House. He edited the Irish Bulletin, did some gun running and was executed as a traitor by the Irish government in 1922. Not a peaceable neighbour.

In contrast to County Wicklow and rural Angus, Burgh Quay is right near the centre of Dublin, on the south bank of the Liffey, a little north of Trinity College. Ireland, and especially Dublin, was not a peaceful place in 1918. And Ethel was Irish at heart, as seen by the note wrapped round the stone she threw at the Wallace Monument “A Protest from Dublin” and by her references to Irish political friends/acquaintances such as Tim Healy MP. In September/October 1917 the funeral march of Thomas Ashe (president of Irish Republican Brotherhood, imprisoned, force-fed and died) must have passed Ethel’s front door. Though whether she had moved in by then is not known. A few years later on, Kay Boyle’s roman á clef [iii] relates that Ethel claimed to have sat with Terence McSwiney as he died in October 1920 in Brixton Gaol. There were big crowds outside the Gaol, and McSweeney was given the first London funeral for an Irish martyr, in Southwark Cathedral. Was Ethel really inside, or was she merely part of the crowd?

Could she have sat quietly in the centre of Dublin, simply painting? I have found no evidence that she was involved in the political or military activity of the time. (But, as said above, there is no record of her paintings either.) Her name is not mentioned in books on the subject, nor on prisoner lists from the local jails – though she was ever partial to aliases. But still….

There was a branch of Cumann na mBan in London when Ethel was there, though this organisation treated women as ‘auxiliaries; suitable for dealing with tea and bandages – not Ethel’s cup of tea. And there were many who were involved in both the suffrage campaign and the Irish independence movement, who travelled back and forth between England, Scotland and Ireland. There were some doughty women about; two were Maud Gonne and Constance Gore-Booth / Lady de Markievicz, both contemporaries of Ethel, both active in suffrage and in the arts, both students at the Académie Julian in Paris at about the time Ethel was there.

Maud Gonne helped found Daughters of Ireland- Inghinidhe na hEireann – in 1900, with twin objectives: freedom & votes for women – both dear to Ethel’s heart. Her husband had fought for the Boers in the Irish Transvaal Brigade in S. Africa and may well have met Ethel’s brother George. Gaunt now and wearing mourning for Ireland, Maud was an individualist, who travelled around complete with dog, parrot, ten canaries, a monkey and a cat!

Constance Gore-Booth was born into the aristocracy in 1868. Aged 24 she went to study painting at the Slade School of Art in London, She became politically active and joined the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She met her husband in Paris; the couple settled in Dublin in 1903, moving in artistic and literary circles and helping to found the United Artists Club. Then at forty (1908) she played a dramatic role in opposing Winston Churchill’s election to Parliament, at which point he moved his efforts to Dundee. Maybe she followed him – at least to rally the troops in Dundee. She also joined Daughters of Ireland and Sinn Féin. [iv] Con used to cycle round Dublin on an old bike, wearing a black bonnet with cherries. She was a terrible show-off.

Ethel already knew Charlotte Despard through their link at the National Service Organisation in London. By now Charlotte was was in her seventies, a long-faced woman who dressed in black, wearing sandals and with a mantilla on her greying topknot. She had worked in London, joining the WSPU, then later the WFL. She stood for Labour in the 1918 election, winning 33% of the vote – not bad for a woman known as a pacifist – but was back in Ireland the following year, active as ever.

So much for politics: such evidence as exists suggests that Ethel had returned to painting as her chief occupation. A woman central to Dublin’s arts world at the time was Sarah Purser.

Sarah would have been coming up for seventy, a lady with a kind heart but a sharp tongue, and a great de-bunker. She too had studied at the Atelier Julien, though 30 years earlier. Living in Dublin, she amassed a huge fortune through smart investments and many portrait commissions.

With Lady Gregory’s nephew the art dealer Hugh Lane she founded the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in 1908. She also co-founded the United Artists’ Club and a stained glass workshop, An Túr Gloine. By 1916 she was living in Mespil House, just north of the canal, where (especially in the ’20s) she held ‘Second Tuesdays’: afternoon receptions for 50-100 literary & artistic guests. It’s hard to think that Ethel would not have attended those ‘Second Tuesdays’.

And that’s all that is known about this time in Ethel’s life. There is no evidence of interaction with her Irish relations. From 1922 to ’26 Ethel was listed as living at 36 George St, Edinburgh. However it is quite likely that she moved from place to place during these years; certainly while she had the Edinburgh flat she was largely in France.

In the early 1920s she was definitely in France, very likely with Fan Parker. Fan had been working as Deputy Controller of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (which was formed in January 1917) in Boulogne, where there was a signals office. Fan’s mother was chairman of the Women’s Imperial Defence League and became commandant-in-chief of the Women Signallers Corps, so probably Fan had been working in that signals office. She was twice mentioned in dispatches, and was awarded the military OBE.

References

[i] S.O. No.24292/157

[ii] The first Lord Kitchener was drowned in June 1916; it is not clear which Kitchener was being referred to here.

[iii] Year Before Last chapter 28

[iv] Con used to cycle round Dublin on an old bike, wearing a black bonnet with cherries. She was a terrible show-off. [Art in Dundee 1867-1924 – Jarron 2015]