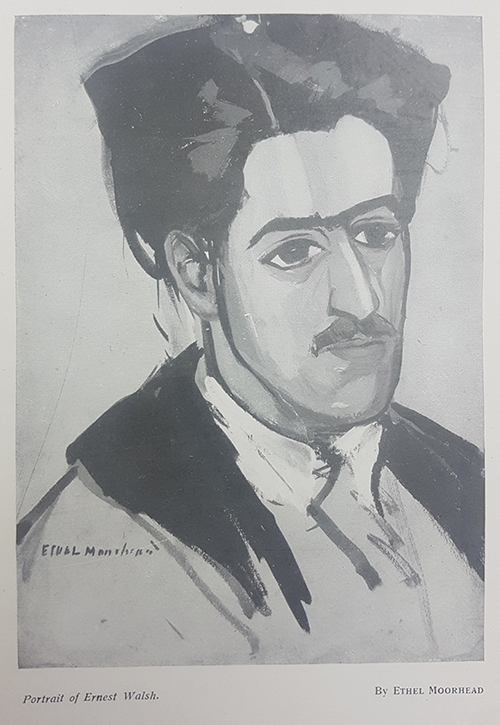

One day in 1922 Ethel was in Claridges Hotel in Paris when she met a young Irish-American poet who was staying there, a protégé of literary critic Harriet Monroe, called Ernest Walsh. He was 24, had heavy dark hair, a dark brow, a gentle expression, a flamboyant and enthusiastic manner, huge gaiety and a great gift of the gab. And Ethel fell for him. We do not know for certain if she actually became his mistress or simply loved, liked and admired him, but at any rate she befriended him immediately.

Ernest had tuberculosis; he had been invalided out of the American air force after an accident which exacerbated his condition and lived on a Veterans’ Bureau pension of $100 a month, which he usually spent well before the next instalment was due. He was a protege of Harriet Monroe (“HM”), whom he had known in the USA, an American widow in her sixties who was a poet, editor and patron of the arts. She knew that new poets had little chance to become known and earn money; few books by living poets were published, and magazines bought poetry mainly to fill leftover space. So she solved the problem by starting her own poetry magazine, Poetry in 1912. Not only had she published some of Ernest’s work, she had got his pension organised for him – $3,000 back pay and a lifelong monthly allowance. But despite the fact he was staying in an expensive hotel he was penniless already because he had lost his money on the way to France, his pension had not yet come through to his new address and the hotel had seized his luggage (five brand new suits and a chamois cape). Ethel bailed him out. (He had appealed to Harriet Monroe and Ezra Pound too and probably got money from them.)

It was a hot summer that year and the doctor said Ernest should not stay in Paris, so Ethel took Ernest under her wing and the pair of them travelled around Europe for a year, through Germany, Italy, Sicily, Tunis, Algiers and back to the Riviera. He didn’t like to go sight-seeing, just to sit in a café with good company and wine. (Ernest, by the way, didn’t like his name and preferred to be called Michael.) They moved a lot because hoteliers were not keen on accommodating them once they discovered Ernest had TB. The summer of 1923 they and Fanny Parker spent in Ethel’s home, 36 George St, Edinburgh. Harriet Monroe came to visit and Ethel hosted a reading of “Modern Poetry” for her, and some of Ernest’s poems were accepted for Poetry. This was a great step forward for him: he was in the company of writers such as Carl Sandburg, Rabindranath Tagore, Vachel Lindsay, Rupert Brooke, William Carlos Williams and Robert Frost.

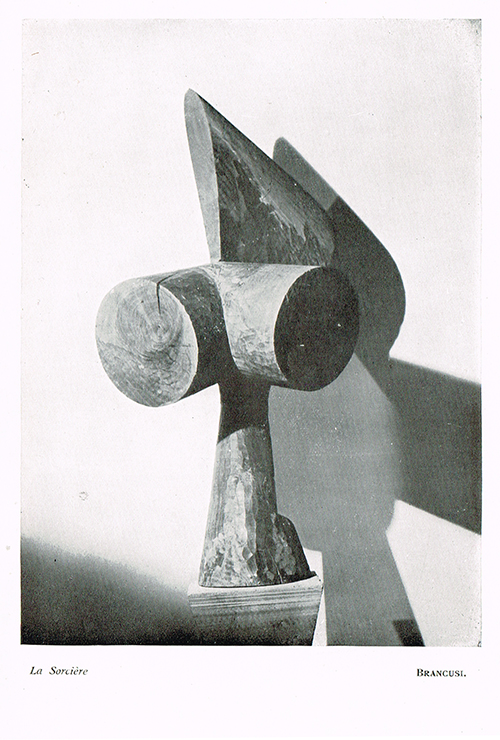

Ernest suffered a series of haemorrhages that summer, and doctors and nurses attended him for eight weeks; the American Consul called round, but did not offer any financial help. In 1927 Ethel was to launch a diatribe against the US Government, claiming that the government had a duty of care to Ernest as a disabled war veteran but had done nothing. Winter came, and off the three went again to warmer climes. They went to Arcachon, near Bordeaux, as recommended by Constantin Brancusi, the Romanian sculptor they had come to know in Paris through Ezra Pound. Ernest was recovering from his bout of haemorrhaging but was still very ill and it seems Fanny was in bad health too. For on 19th January 1924 Ethel’s dearest friend Fanny died at the age of 48.

Ernest wrote a poem in memory of Fanny –

TO MOURNERS

Grieve under darkness

weep no louder than

Muffled wheels of thunder

where you would follow appears

A slim half-veiled moon

a nun watching her iron shrine.

Do not speak…………..

hear hear whispering:

“These things belong to me.”

Apart from a small legacy to her sister Fanny left her suffrage medal and all her property to Ethel “in grateful remembrance for her care and love”. Her executor was Janie Allan; Ethel recorded later that she was severely disappointed with the manner in which Janie had exercised this function. ‘Her part as executor during these three years she confined to signing certain papers which deprived me of more and more of the Estate. But the arduous clerical work of correspondence with the stupid lawyers and posting them up in the affairs of the Estate, of which they were grossly ignorant, was done by myself.’ Nearly three years after Fanny’s death Ethel still had not received the whole; ‘What is left is gradually dwindling away by lawyers paying themselves, and pandering to yearly increases in taxes, duties, revenue, which make life in Great Britain now impossible.’ One can sympathise with Ethel’s exasperation, but she was clearly a lady difficult to get on with. ‘Had Miss Allan been a patron of, or interested in the arts, she would perhaps have exerted herself…’ [i] This of a woman who had been a good and helpful friend; why does money have such a capacity for causing ill feeling?

In expectation of this legacy Ethel and Ernest decided to co-found a literary magazine ‘because he believed in himself. Because I believed in him and his poems.’ It was to be a quarterly review of the arts called This Quarter and its objective was ‘to publish the artist’s work while it is still fresh’.

At this time there was a host of small magazines written, edited and published by the literary circle in Paris. Shari Benstock, in Women of the Left Bank, writes that many magazines developed round “-isms”, each with its own clique, and women were largely excluded from the cliques so found it difficult to get published; surrealism, for example, was a misogynist movement. So quite a few women, writers themselves, (Nancy Cunard, Caresse Crosby, Maria Jolas, Florence Gilliam, Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier as well as Ethel Moorhead) set up small presses or edited magazines. But they did not receive the serious attention accorded to the men – their efforts were seen as a function of their roles as wives or lovers. Many references to This Quarter were to name Ernest as sole editor. Gertrude Stein was ‘The only woman to assume a central place in the literary hierarchy of the Paris community.’ [ii] [iii] On the other hand This Quarter never made a particular effort to feature women, and only published (apart from Ethel herself, Fanny Parker and Kay Boyle) six other women, compared to fifty-three men. By contrast, James Charters (Jimmie the Barman) considered that women were the leaders and organisers of Montparnasse [iv] – perhaps more of the social world than the literary one?

Meanwhile, Ethel had to return to Edinburgh to settle some affairs, possibly relating to Fan’s death. Scotland would have been too cold for Ernest so he went to San Diego, California. He fell in love, Ethel said, but “she was afraid of his illness”, and by May he was back in Europe. They spent the summer of 1924 first in Edinburgh, then in Switzerland, but the poet found the mists over Lac Leman depressing, so they journeyed to Italy, where they became friends with Carnevali.

Emanuel “Em” Carnevali was an Italian poet and writer in his late twenties who had made his name in the USA after emigrating when he was 16. He made friends but never made money, and in 1922 he became ill, a nervous disorder later diagnosed as encephalitis lethargica which was epidemic at this time, that caused him to shake and convulse continually. He returned to Italy, (“O Italy, O great boot, / don’t kick me out again!”) to a hospital in Bazzano. He was despondent and disillusioned, as expressed in

Fireflies

Fireflies flying disconnectedly,

useless lights that bear no light to anything,

whose little lamps make the night darker.

You are one of the many useless works of God,

but still you are not beautiful;

but for the star

you carry in your belly,

you would look like a common insect.

You carry a bit of my soul in that lantern of yours.

You are like my weariness,

aimless and desultory.

His friends did their best to cheer him up and support him. He was visited by many in the modernist literary circle including Harriet Monroe and Ezra Pound. Kay Boyle bought him a radio, Ernest Walsh gave him a gramophone, and Robert McAlmon had him moved to a private sanatorium and paid a year’s fees. (possibly more; Ethel says funding dried up in 1929.) His first book was to come out in McAlmon’s Contact Editions later in 1925. In 1929 Ethel set up a fund for him, to save him going back into the charity hospital. He lived until 1942 but he never got out of hospital.

The autumn of 1924 saw Ethel and Ernest in Rome, and by October they were back in Paris. Ethel had been working on the first edition of This Quarter all year, and as editors they both probably wanted to meet with some contributors, although a fair amount of work was done by post. After that they went to Pau in the Pyrenees, and Chamonix; (one of Ernest’s poems was written from there). Ethel recalled that time in her later Memoir: ‘[He] typed, and rarely changed a line. When the poem was written he would ask me to read it aloud to him several times. He was not a great reader and did not own many books. But during successive illnesses I read to him all the novels of Dickens … did not sound false when competing with death…’

In those days Montmartre, on the left bank of the Seine, was the place where artists gathered, and there was a large number of young aspiring Americans with their own literary clique. They stayed in small cheap hotels or lodgings along the place St Germain des Prés, slept late, spent hours sitting on café terraces talking and drinking, fell into bed well oiled. Americans loved Paris as an escape from home. They loved the 18th and 19th century architecture, the clatter of school children’s wooden soled shoes, the little dance halls called bals musettes, the good food and wine …. At the heart of the ex-pat community was Sylvia Beach’s book shop ‘Shakespeare & Co’, where they gathered to talk and read their new work as well as to borrow books. The shop was also used as a poste restante, and at one point the composer Antheil (of whom more later) was living in the room above.

On the opposite side of the rue de l’Odeon stood ‘Maison des amis des livres’ run by Sylvia’s friend and mentor Adrienne Monnier. It is surprising how little American and British writers refer to any of the French set in their memoirs, although McAlmon mentions many in his endless list of names in Being Geniuses Together; there was certainly interaction but the French as a whole were still recovering from the war and rather resented the influx of rich foreigners.

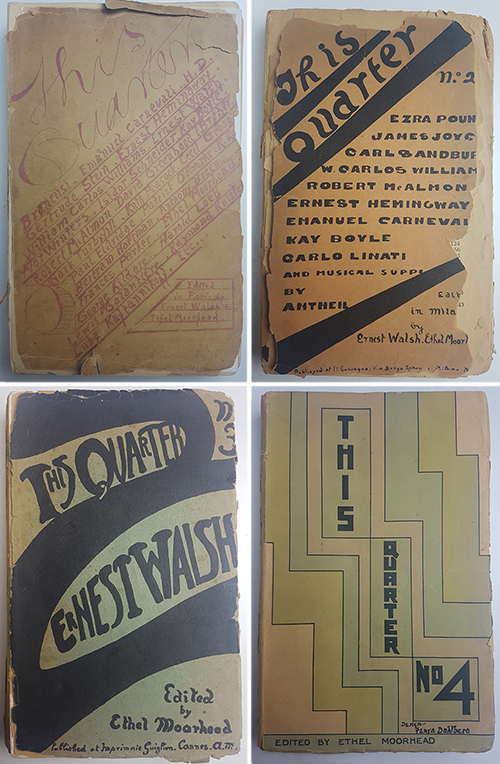

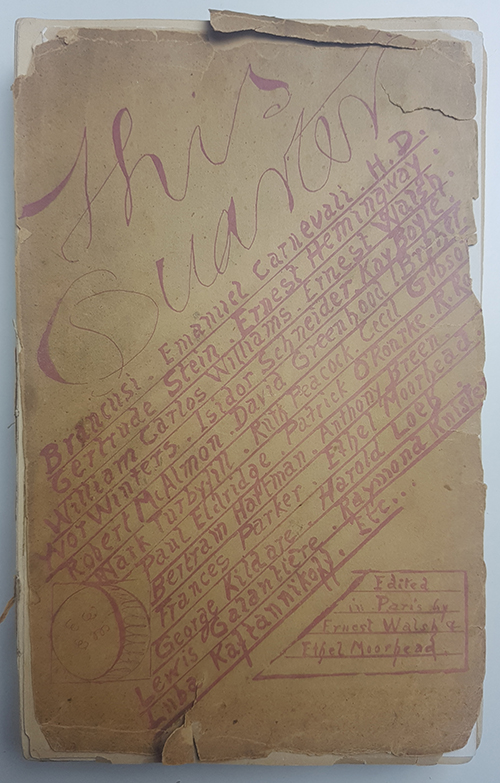

The first edition of This Quarter was published in Paris in May 1925. The editorial, by Ernest, is exuberantly over-the-top. “We warn all critics, labellers, baptisers, slanderers, experts, reviewers and such to be slow in giving us a number or letter or any documenty classification lest they be confounded. We are fickle, wayward, uncommitted to respect of the respect of the respectable established armies strong because many.” He goes on to ask for money from readers in order to increase the payments given to contributors; “Don’t exploit his [the artist’s] idealism… Artists, as well as golf clubs and scientific colleges, and new parties, are building civilisation. Put us in your budget. Send a simple cheque to THIS QUARTER.” Ethel echoes these sentiments in This Quarter 3 [v]: “In THIS QUARTER we have the faulty writer, the irreverent experimenters, the joyful law-breakers of literature, painting, sculpture, music, – Don Quixotes, Robinson Crusoes, moths, crocodiles, leopards…”

The magazine was distributed in London and Paris and bookshops all over the USA, and was well regarded, with contributions from Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Emanuel Carnevali, William Carlos Williams and (of course) Ernest Walsh, as well as many less well known names. One contributor was a poet called Anthony Breen, of whom all I know is that he came from Portarlington; perhaps an old friend. Another was a 22-year-old American writer Kay Boyle, of whom more later.

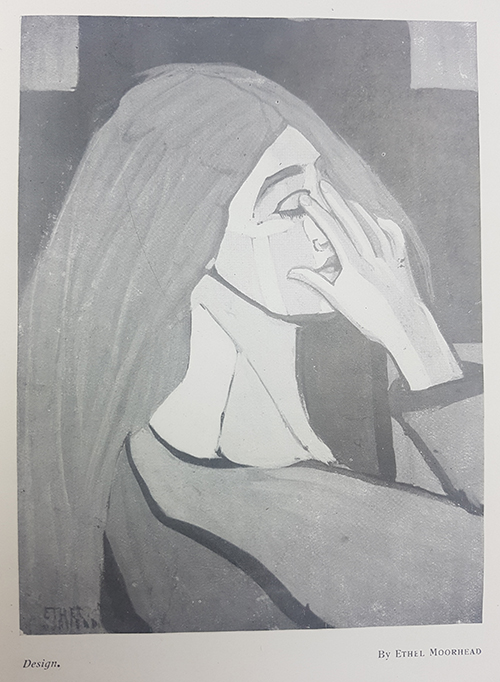

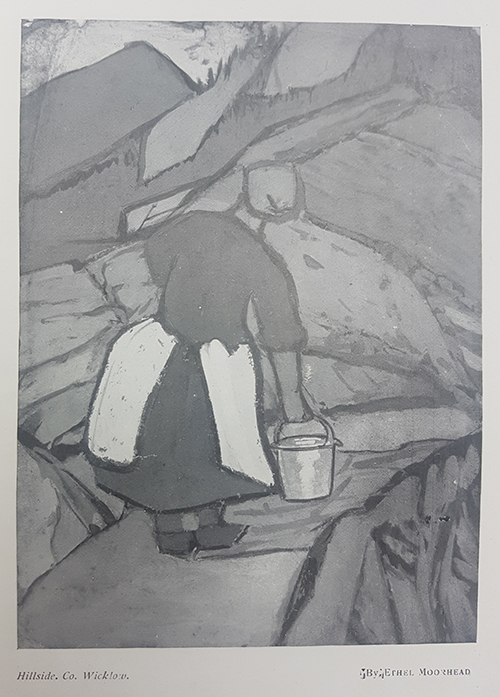

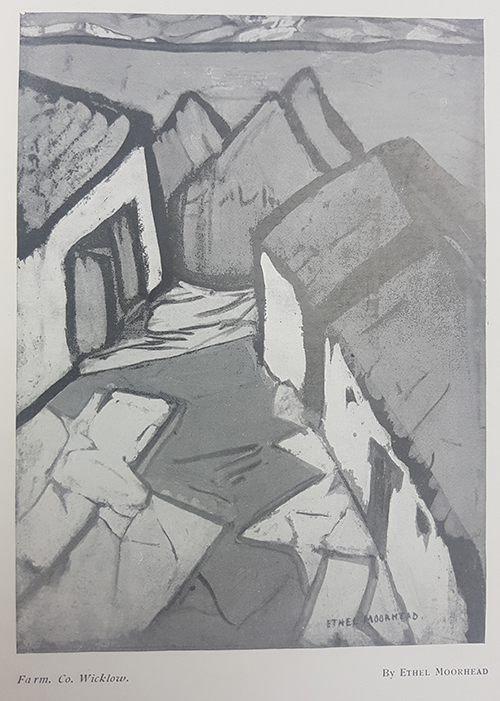

The arts supplement features drawings and sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, an abstract sculptor associated at that time with the Dadaists. There are also four paintings by Ethel, three by Bertram Hartman (42-year-old American painter) and two by Fan Parker. The latter are rather undistinguished, their inclusion probably a mark of friendship and love; there is also a poem by Fan. Ethel’s paintings are two portraits (one of Ernest) and two County Wicklow landscapes; it is a pity that these are reproduced in black and white as they would probably have been in strong colours. Her written contribution, apart from the tribute to Pound, was restricted to a review of Robert McAlmon’s book Village.

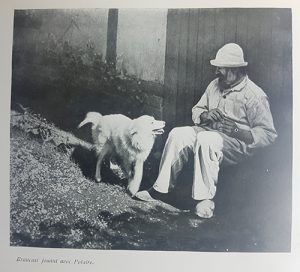

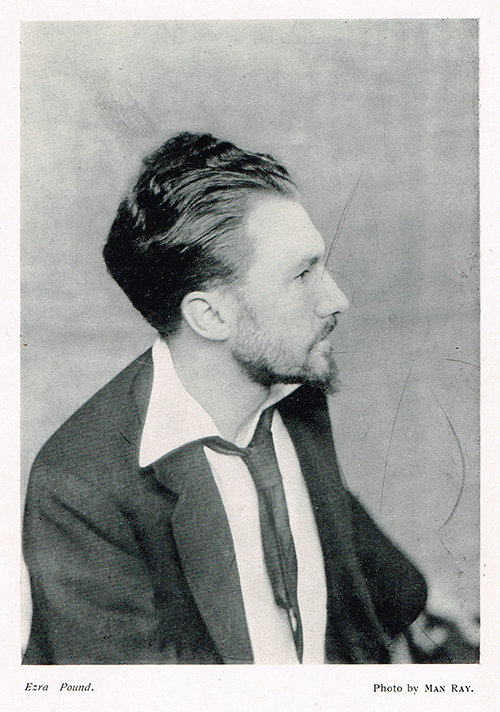

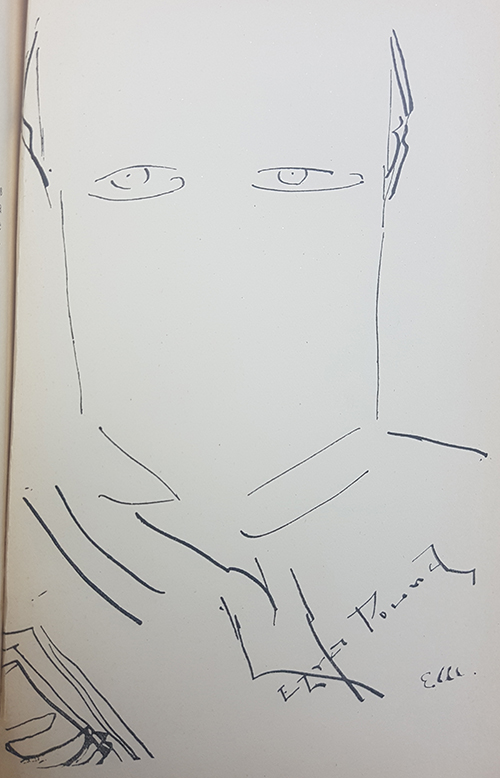

The first edition was dedicated to Ezra Pound, with tributes from Hemingway and James Joyce. Harriet Monroe had given Ernest a letter of introduction, and Pound had become his patron. The dedication to Pound runs “….who by his creative work, his editorship of several magazines, his helpful friendship for young and unknown artists, his many and untiring efforts to win better appreciation of what is first rate in art comes first to our mind as meriting the gratitude of this generation.” The volume is fronted by a photograph of Pound by Man Ray and an impressionist sketch by Ethel herself.

Ezra Pound, born in Idaho, came to London and was hired in August 1912 by Harriet Monroe as a regular contributor to Poetry, enjoying success early in his life By 1926 he was forty years old, good looking, with red hair, high cheekbones and a wispy beard; he was serially unfaithful to his wife; and he was pretty pleased with himself. Since he had become his patron Ernest’s tribute is of course glowing, though even he admits “Not everyone likes him. No man of character has ever been a universal favourite.” Nevertheless he certainly helped many young writers; he helped to get James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man serialized in The Egoist and then published in book form, and he persuaded Poetry to publish T. S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in June 1915.

Ethel had only met him twice, the first time being when he came to visit Ernest, who was sick. Her impression was of a big man with a big personality and rather intimidating. “If a psychologist or mesmerist had afterwards said familiarly ‘Ezra’? I would not have answered poems, cantos, sonatas! I would have said “Eyes…color… cadmium…amber…topaz in Chateau Yquem!” The second time they met was after lunch one day on a Left Bank boulevarde. He looked merry and ‘I perked up, and because I knew he had been ill I asked him if he was better now. Ezra Pound said sonorously ‘I was ill. I am better.’”

However, the relationship deteriorated over time. In the spring of 1925 when Ethel and Ernest were visiting Emanuel Carnevali in Bologna they saw Pound again. At that time they were working on the second edition of This Quarter; they did not ask Pound to contribute because he had refused an invitation for the first edition. He was nevertheless very keen about the magazine, Ethel said, but he “had a bogey that we would ask him for some charity. … He repeated often that he had ‘done so much for CHARITY’ and that ‘he could do no more for CHARITY’”. So Ethel and Ernest concluded that Ezra was hard up, and they planned to help by buying buy a canto of his. They were “truly flabbergasted” (Ethel’s words) when Pound asked for £40. This was way over the going rate, (they normally paid 40 francs/12 shillings per page) but by then Pound was well recognised, so they agreed to pay, even though this meant some lesser known writers had to wait for their money. Cantos XVII-XIX were duly published in This Quarter 2.

A friendly correspondence between Ernest and Ezra ensued, and when some months later Ernest and Ethel were in Italy they went out of their way to visit Ezra in Rapallo, where he had fled with his wife for quiet and warmth. “He was then full of suggestions for THIS QUARTER,” Ethel wrote in 1927 in This Quarter 3, “but afterwards, because his advice and suggestions were not taken up, his friendship cooled. And when Ernest Walsh sent him a group of his poems last summer, asking for the kind favour of a criticism, Ezra Pound did not even reply. Ernest Walsh greatly valued Pound’s opinion and he was worried during those last sad months of his illness that Pound had not replied. But he was thoroughly disillusioned about Ezra Pound before he died and spoke bitterly of him as an exploiter… Ezra Pound kept these poems three months… and Ernest Walsh was dead when he did reply … And after Ernest Walsh’s death Ezra Pound wrote to this editor like an ignorant clown, saying ‘he did not know to whom he should express regret’ and he did not express it… And when I asked him to return Ernest Walsh’s poems he wrote that ‘HE couldn’t do anything about the poems. HE couldn’t suggest any publisher who would handle them, HE couldn’t advise anything.’. This presumption is characteristic of Ezra Pound: his anticipation of a request and the warning that it is no use to make it! Now, I am Ernest Walsh’s literary executor, I did not ask either advice or help, or suggestions from Ezra Pound.”

However Ethel did ask Ezra to write a tribute to Ernest for publication in This Quarter. Pound replied that he would write, but that a tribute ‘elsewhere’ would do more good. At this time Pound was bringing out a new magazine of his own called The Exile; Ethel presumed this was where the tribute would be, but there was never a word. For Ethel, distraught by Ernest’s death, this was the last straw. “I herewith take back that dedication… We take back our too-generous dedication.”

The avant-guarde literary circle was effectively based in Paris, but it swirled around southern Europe as well. They all knew each other – Ethel’s nephew in S. Africa reported that their aunt “was mixed up in a coterie of writers” – so many contributors to This Quarter were friends, or at least acquaintances. A snippet in This Quarter 1 [vi] shows the artists’ circle as Ethel knew it:

Many sighs about civilisation these days.

Well get Ezra Pound, Brancusi, Hemingway, McAlmon, Gertrude Stein, Carl Sandburg, ZADKINE, George ANTHEIL, HD, Wyndham Lewis, RENATA BORGATTI, Emmanuel Carnevali, BERTRAM HARTMAN, Ethel Moorhead, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, SHAKESPEARE & CO, William Carlos Williams, Yvor Winters, Charles Chaplin, Ernest Walsh, BRYHER, Mina Loy, Norman Douglas, May Sinclair, Dorothy Richardson, T.S. Eliot, Alfred Kreymborg, Harold Loeb, Olga Rudge, Donald Ogden Stewart, Frank Conroy, Margaret Anderson, Hariet Monroe, Jane Heap, Lola Ridge and Ring Lardner, get them, get them together, organize, buy Corsica with all its fittings or any other suitable spot untroubled by Prohibition, Censors, Taxes and high cost of living, buy this place and then wait to see what these people living there together would do. Perhaps in a year the colony would be known as THE KORSIKA-KRAFTERS. Perhaps it wouldn’t ….

Kay Boyle observed how ex-patriates seemed to gravitate together, in a world where many of them (including Ernest) did not even speak French. 60% of This Quarter’s contributors came from North America; they were dubbed the “Parisamerican circus” by John Herrman. They were a young set: Gertrude Stein, who was a bit older, was pretty scathing: “All of you young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation…. You have no respect for anything. You drink yourselves to death”. Apart from Gertrude Stein, Ethel was more than a decade older than any of This Quarter’s writers. Moorhead family gossip has it that “colourful artist sister Ethel was not only an enthusiastic member of Emily Pankhurst’s band of suffragettes but also notched up numerous affairs with the well-known Bohemian personalities of the era.” But gossip is not necessarily true.

One friend Ethel and Ernest saw often was Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway was now 26; he had married his first wife Hadley in 1921, and the couple came to Paris at the end of that year. He was tall and handsome, an endlessly competitive ‘outdoor’ man – fishing, boxing bull-fighting etc. – and also one of the few American writers in Paris at the time who actually earned a living by writing (journalism).

Nevertheless, when they had sent him the prospectus for This Quarter in Austria, he had responded with the story Big Two-Hearted River and was paid 1,000 francs. Hemingway was a big help in producing This Quarter 1. He loved fixing things, and was often to be found at the Imprimerie of Herbert Clarke in rue St Honoré, a rather small run-down printers where rats ate the rollers! It was Hemingway who obtained the frontispiece photo of Pound and Hadley who proof-read. He thought This Quarter was ‘a class magazine’.

Hemingway thought Ernest was a poseur of little talent, ‘… a fraud, running from both death and creditors’ and he was sorry for Ethel, for her sincere affection, which would forgive ‘her’ Ernest anything. In “A Moveable Feast”, published in 1964 he was to describe Ernest cuttingly: Foppish, with black Irish eyes deep in sallow face and a big-toothed smile, a charmer of women. Hemingway met him in Pound’s studio, the day he arrived in France, trailing two young women in mink coats whom he had picked up onboard. “Ernest Walsh was dark, intense, faultlessly Irish, poetic and clearly marked for death as a character is marked for death in a motion picture.” He had told the girls a pack of lies, and later was to lie to both Hemingway and James Joyce about giving them a poetry award from This Quarter. But “certainly nothing could ever be said or imputed against Walsh’s co-editor.” “[Ernest] gave me complete, sad Irish understanding and the charm. So I was always very nice to him and to his magazine, and when he had his haemorrhages and left Paris, asking me to see his magazine through the printers, who did not read English, I did that and it pleased me at that time, which was a difficult time in my life, to be extremely nice to him, as it pleased me to call him Ernest. Also I liked and admired his co-editor. She had not promised me any award. She only wished to build a good magazine and pay her contributors well.”

Another friend who played a large part in Ethel’s and Ernest’s life, and who was published in every edition of This Quarter, was Robert McAlmon. Among American expatriates in Paris during the 1920s, McAlmon was regarded as a writer of significant talent and potential. By the time he was nineteen six of his poems had been published in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry Magazine, but he never did as well as Ernest Hemingway and many of his other associates did. Benstock [vii] describes him as unself-critical, dissolute, an easy mark for spongers and never taken seriously. Then too commercial publishers were unwilling to distribute his work, at least in part because of his honest treatment of homosexuality.

In the USA McAlmon became a close friend of William Carlos Williams, with whom he founded the literary magazine Contact in 1920. Then he married Annie Ellerman (literary name Bryher), the daughter of a British shipping magnate and they journeyed to Britain. Bryher was lesbian (McAlmon was bisexual) and refused to consummate the marriage; he went on to Paris alone. Cynical about human relationships he took to the booze. In 1923, with money the Ellerman family gave him, he started Contact Editions to publish innovative works.

In 1925, McAlmon published five important books. One was his own, Distinguished Air: Grim Fairy Tales, which was immediately hailed by Joyce, Pound, and other leading modernist writers as the author’s most important work to date. One was Carnevali’s A Hurried Man. Another was Gertrude Stein’s Making of Americans. Unfortunately the financial problems involved in this latter meant that Contact Editions closed in about 1930.

McAlmon and Kay Boyle were very good friends, and co-wrote a book about their life at this time called Being Geniuses Together, finally published in 1938. His opinion of Ethel (p.251) was that she was a good literary critic: “Ethel had a critical instinct which was keen, but she let personal likes and dislikes influence her critical sense too greatly… publication [of This Quarter] was erratic as to appearance as well as to editorial approach”

But to return to the summer of 1925. Ernest and Ethel had gone to Pau, but very possibly returned to Paris for publication date. This Quarter 1 was published in May from 338 rue St Honoré in Paris. It made its mark; it sold out. The autumn of 1925 saw Ethel and Ernest in Como, Chillon (Lake Geneva) and then Milan, bringing out the second edition. Ernest’s medical board in Milan had advised more warmth for him, so straight away they finished off the proofs for the printer (although This Quarter 2 was not published until over a year later) and took the train to Grasse where Ethel rented a villa. The house had belonged to a corrupt businessman who had made his fortune selling shoes with paper soles to the troops; the toilet on the second floor flushed mysteriously of its own accord every ten minutes or so. Ernest took to his bed, and with few visitors, absolute rest and proper food he soon made progress. In a letter to his friend Kate Buss a few years earlier [viii] Ernest spoke fondly of Ethel having nursed him “with unequalled devotion.” “My debt to her is too great to ever repay.” They were undoubtedly very fond of each other, their blazing rows all part of their complex love. He was bedbound for three months until Jan ’26. It was then that he composed his own invented ‘Old English’ – poems which were to be published in This Quarter 3. “They were written in the mornings, in a few minutes, very quickly. … He rarely altered a word. And when the poem was written he wanted it read to him. I would read them many times. He himself read poetry most perfectly, without self-consciousness – belonging to the poem. … He was happy then, cheating his enemy death, writing these poems – and they were the last of his happy days.” [ix]

References

[i] This Quarter 3, p. 271

[ii] Women of the Left Bank – Shari Benstock Virago 1987

[iii] Clearly Stein expected this lofty position; in 1925 Miss Stein said “Yes, the Jews have produced only three originative geniuses: Christ, Spinoza and myself.” – Exile – Pound 1938

[iv] Being Geniuses Together p.49

[v]This Quarter 3 p.256

[vi] This Quarter 1 p. 255

[vii] This Quarter p.255

[viii] 27.11.22

[ix] “A Memoir by Ethel Moorhead”. Ernest’s Poems and Sonnets was finally published by Harcourt Brace & Co in 1934.